Recently, I came across a collection of papers published by DeepSeek, documenting the evolution from the first version of DeepSeek’s LLM to the latest R1. From today’s perspective, we know that DeepSeek R1 has reached a level close to the industry’s leading models. However, what intrigues me more is how it evolved from a quant company in China that was initially overlooked to where it is now.

In this series of blog posts, I will attempt to trace their exploratory trajectory from a paper-reading perspective, following the path of DeepSeek LLM -> DeepSeek MoE -> DeepSeek V2 -> DeepSeek V3 -> DeepSeek R1. While organizing the papers, I discovered that DeepSeek’s first publicly released paper was in January 2024, when they had just released their first version of the model. Even within the AI industry, they were not considered a major competitor at that time. Yet, just a year later in January 2025, they had evolved to the leading-edge level of R1. It is often said that in AI, a day is like a year in the human world. But when you actually see the progress made in a year, it is truly awe-inspiring how fast DeepSeek has advanced.

Background

DeepSeek LLM was the first LLM open-sourced by DeepSeek. At that time, the most popular open-source LLM was LLaMA-2, and many models were based on its architecture and foundation. From a retrospective perspective, we now know that DeepSeek eventually chose a MoE architecture different from the Dense architecture of LLaMA. However, in the first version, they essentially copied LLaMA-2’s architecture with some local adjustments. It can be inferred that the team was still in the exploratory phase regarding model architecture at that time.

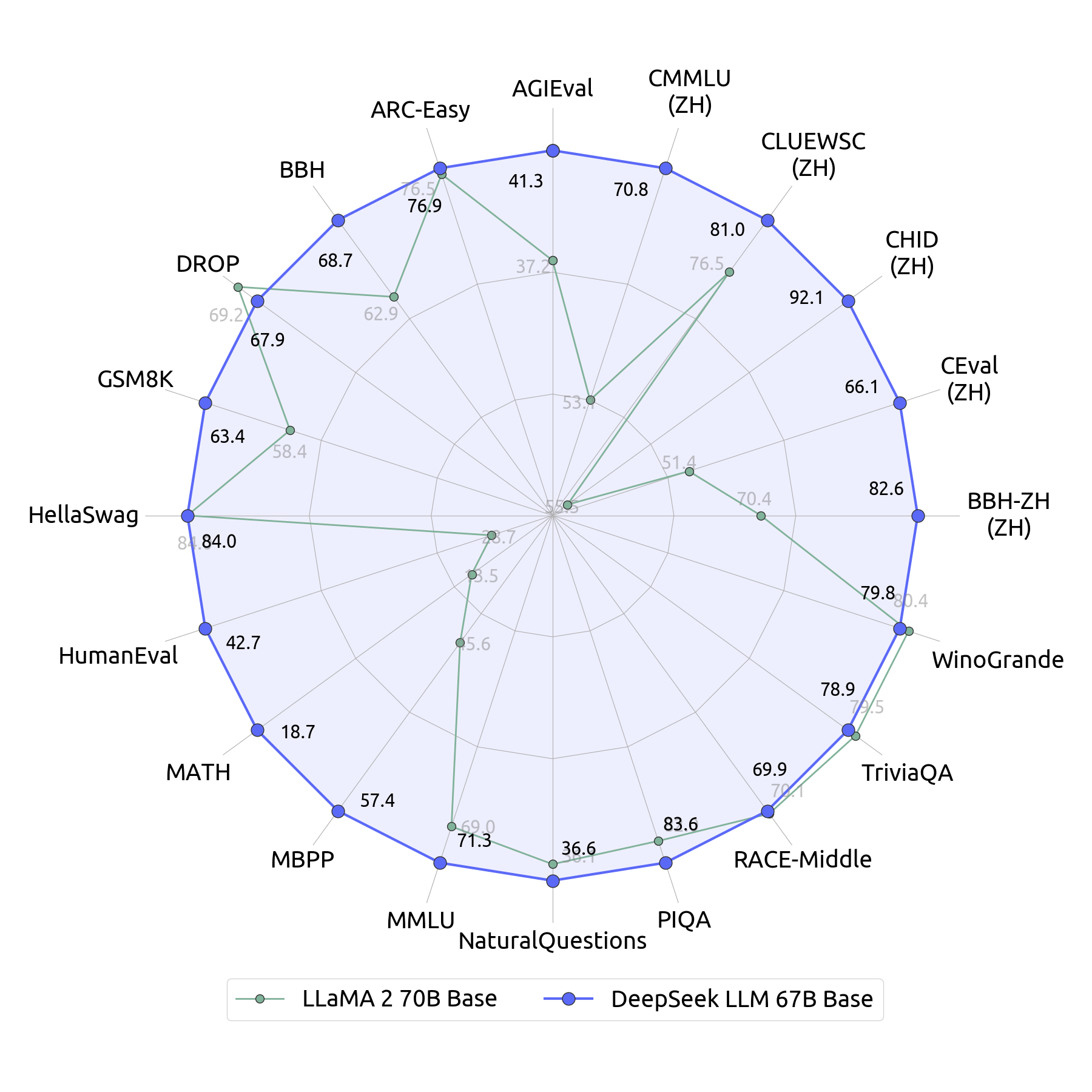

Although the architecture was largely the same as LLaMA-2, with both trained on 2T tokens, DeepSeek LLM outperformed LLaMA-2 comprehensively in performance evaluations, as shown in the image below. The paper introduced some interesting findings about data, training, and fine-tuning methods.

It is noteworthy that DeepSeek could have used more data and larger models during training, which would undoubtedly improve model performance. However, the purpose of this paper was mainly to compare with LLaMA-2, so they intentionally kept the data scale and parameter size as similar as possible to focus on other areas for improvement.

Data

There were significant differences in data selection between LLaMA-2 and DeepSeek LLM. Although both used 2T tokens, LLaMA-2 had close to 90% of its corpus in English, while DeepSeek LLM did not specify the language proportions but implied that the ratio of English to Chinese in the corpus was more balanced. Logically, it was not surprising that DeepSeek LLM significantly outperformed in Chinese evaluations. What was unexpected was that in English evaluation metrics, DeepSeek LLM achieved comparable performance despite significantly less training data.

I speculate that there are two reasons for this phenomenon. First, the quality of DeepSeek LLM’s corpus was higher, compensating for the quantity disadvantage. LLaMA-2 mentioned that it did not filter the dataset for sensitive information, while DeepSeek LLM introduced a model to assess data quality, specifically increasing the proportion of data from niche fields to enhance data diversity. Therefore, it can be inferred that the English corpus quality of DeepSeek LLM was higher. For reference, LLaMA-3 also introduced deduplication and quality filtering during data preparation to improve corpus quality.

The other reason I suspect is that the introduction of Chinese corpus also improved the model’s performance in English. OpenAI’s GPT 3.5 was primarily trained on English corpus but performed well in Chinese. A possible reason is that knowledge learned from English corpus was transferred to Chinese. Similarly, knowledge learned from Chinese corpus could be transferred to English. Additionally, since Chinese and English have significant differences in grammar and expression, this diverse data might enhance the model’s capabilities. Furthermore, different languages have distinct cultural backgrounds and content tendencies, further increasing data diversity. If this speculation holds, then preparing the corpus should intentionally increase the proportion of different languages to allow the model to learn richer linguistic expressions.

Model Architecture

In terms of model architecture, DeepSeek LLM was almost identical to LLaMA-2, using the same technologies such as Pre-Norm, FFN activation functions, and positional encoders. The biggest difference was the use of GQA (Group Query Attention). Compared to the original MHA (Multi Head Attention), GQA can be understood as a method to save training and inference memory usage by allowing multiple Query heads to share a set of Key and Value parameter matrices, significantly reducing memory consumption. However, this comes at the cost of reducing the number of Key and Value latent spaces, thereby diminishing the model’s expressive capabilities. LLaMA-2 addressed this by increasing the width of the FFN network to provide more nonlinear expressive capabilities, while DeepSeek LLM chose to increase the number of Attention layers. Roughly speaking, although the model parameters were the same, LLaMA-2 was a wider model, and DeepSeek LLM was a deeper model. From a retrospective perspective, DeepSeek’s subsequent MLA introduced in V2 made a radical update to the Attention layer, directly reducing the KV Cache required for inference by an order of magnitude.

Another difference was that LLaMA-2 used a cosine learning scheduler, while DeepSeek LLM used a Multi-Step learning scheduler. The reason given was that when increasing the amount of data, Multi-Step could better utilize the results from the previous stage, allowing for faster continuous training.

The paper also spent a significant amount of space explaining how to choose appropriate hyperparameters under different data scales, data qualities, and model sizes, and how to draw scaling law curves. This was presented as the biggest highlight of the paper, but it felt like alchemy to me, giving me a headache. Interested readers can check it out themselves.

Post-Training

At the time of the paper’s publication, post-training mainly involved alignment, using SFT and RLHF to align with human preferences and increase model safety. The data used were mostly labeled conversational texts, with no special processing of the data distribution. DeepSeek LLM made a very different choice in data selection compared to LLaMA-2.

If you look at the model performance evaluation comparison chart at the top, you can see that DeepSeek LLM performed much better in non-Chinese metrics such as MATH, HumanEval, and MBPP. This is because nearly 70% of the samples in DeepSeek’s post-training SFT phase were related to Math and Code. It is evident that they did not prioritize alignment in post-training but focused on enhancing model capabilities, making this more of a sneaky optimization for ranking.

At that time, the mainstream approach was to SFT a code and math-focused model after the base model was trained, such as Code LLaMA and OpenAI Codex, which were SFTed from LLaMA-2 and OpenAI GPT3, respectively. Meta even SFTed a Python-specific LLM from Code LLaMA.

Now we know that performing RL on Math and Code samples during the post-training phase can stimulate the model’s CoT reasoning capabilities, and the idea for R1 might have been born at this time.

Additionally, DeepSeek LLM did not use the popular RLHF at that time but chose DPO (Direct Preference Optimization) for aligning with human preferences. This method directly optimizes the probability difference between two different generation results as the training objective, which is more intuitive and easier to design compared to RL. DPO was also used in the post-training process of LLaMA-3. It is evident that the DeepSeek team was not satisfied with the existing RL algorithms and was still exploring. This led to the later GRPO announced in DeepSeek Math.

Future Work

When I was in school, my teacher told me that real Future Work should not be written in the paper; instead, you should secretly work on it and publish the next paper. The Future Work section in DeepSeek LLM’s paper, from today’s perspective, is too sincere, almost pointing out the path to R1.

DeepSeek LLM will be a long-term project, focusing on promoting the progress of open-source models.

This is hard to say, as it has only been a year or so.

Soon, we will release our technique reports in code intelligence and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE),

respectively. They show how we create high-quality code data for pre-training, and design

a sparse model to achieve dense model performance.

This “Soon” meant releasing MoE in a week and DeepSeek Code in half a month. We now know that MoE became the foundational architecture for V2, V3, and R1, with parameters rising to 671B.

At present, we are constructing a larger and improved dataset for the upcoming version of

DeepSeek LLM. We hope the reasoning, Chinese knowledge, math, and code capabilities

will be significantly improved in the next version

The data volume increased from 2T to 8T in half a year, although LLaMA-3 increased to 15T at the same time. DeepSeek V2’s metrics were slightly behind LLaMA-3 in English, and by V2, their focus had shifted to wildly reducing costs and lead a crazy price war has in China.

Our alignment team is dedicated to studying ways to deliver a model that is helpful,

honest, and safe to the public. Our initial experiments prove that reinforcement learning

could boost model complex reasoning capability.

Looking back from today, this is precisely the most important method of R1.

Conclusion

From today’s perspective, DeepSeek was likely still in the exploration phase, aligning with the open-source models in the industry and conducting theoretical research. However, from the details in the paper, the conditions for the groundbreaking R1 to be born a year later were almost in place.